Many people using Solarplate create negatives on transparencies using an inkjet or laser printer. This approach works well for intaglio plates which don’t require a high contrast negative, but it has some drawbacks – the artwork must be created or scanned and fixed up on the computer before printing and you need a high quality printer and lots of expensive ink cartridges.

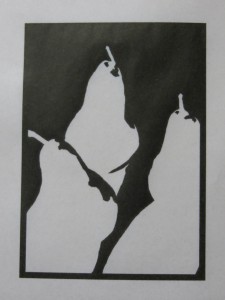

My notans have large areas of solid black, so they more naturally lend themselves to relief printing where the raised portions are inked with a roller and the valleys remain clear. SolarPlate works well for relief printing, but the platemaking process is different because it is essential that all of the photopolymer wash away from the white regions without losing any photopolymer in the black regions. This is important because the photopolymer layer is really thin – typically less than 1mm. Any loss in the relief between the ink bearing plateaus and the white valleys will make it hard to apply the ink to the plateaus without getting it in the valleys.

The key to creating a great relief plate is contrast. To make a plate where the blacks are fully exposed and hardened while the white regions soft enough to dissolve all the way down to bare metal requires a high contrast negative.

I found that my low end Canon IP90v printer was unable to create negatives with sufficient contrast because its black ink is not opaque. If I hold the transparency up to a light, the blacks appear as weak grays. The result is a plate with pitting in the blacks.

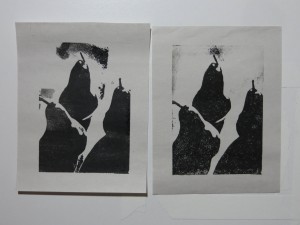

This plate was made with a low contrast negative. When rinsing the white areas down to bare metal I got a lot of pitting in the blacks which weren’t fully exposed.

I switched to painting the negatives by hand using either gouache or India ink on vellum. This approach produced negatives with reasonable contrast, but the plate actually picked up the texture of the unpainted vellum. The texture wasn’t really a problem since it was subtle and only appeared in the raised portions of the plate where it actually helped to hold the ink.

The vellum used for this plate was translucent had a fairly coarse grain that showed up on the plate. Notice how the pattern in the grain reveals the wrinkles in the vellum.

The bigger problem was that on the larger plates, the gouache tended to cause the vellum to wrinkle and warp and this led to a poor reproduction because the vellum wouldn’t stay in contact with the plate during exposure.

This vellum negative wrinkled because of the large expanse of black gouache. Vellum doesn’t seem to wrinkle if the black regions are small. I was able to successfully make a similar negative for a 5×7″ plate, but when I scaled it up to 8×10″, the wrinkles got out of control.

This plate was made from a vellum negative that was warped and wrinkled due to the water in gouache. Notice the ghost images in some areas that were out of focus and didn’t dissolve down to the metal.

I attempted to solve this problem by painting my negatives on materials like mylar and glass which don’t warp, but I wasn’t able to acheive sufficient contrast, even with gouache. It seems that the fibers of the vellum will wick up paint and ink, making a good solid black. The mylar and glass aren’t absorbant, so they don’t hold a very opaque black. I also found that the dried gouache tended to flake off of the mylar.

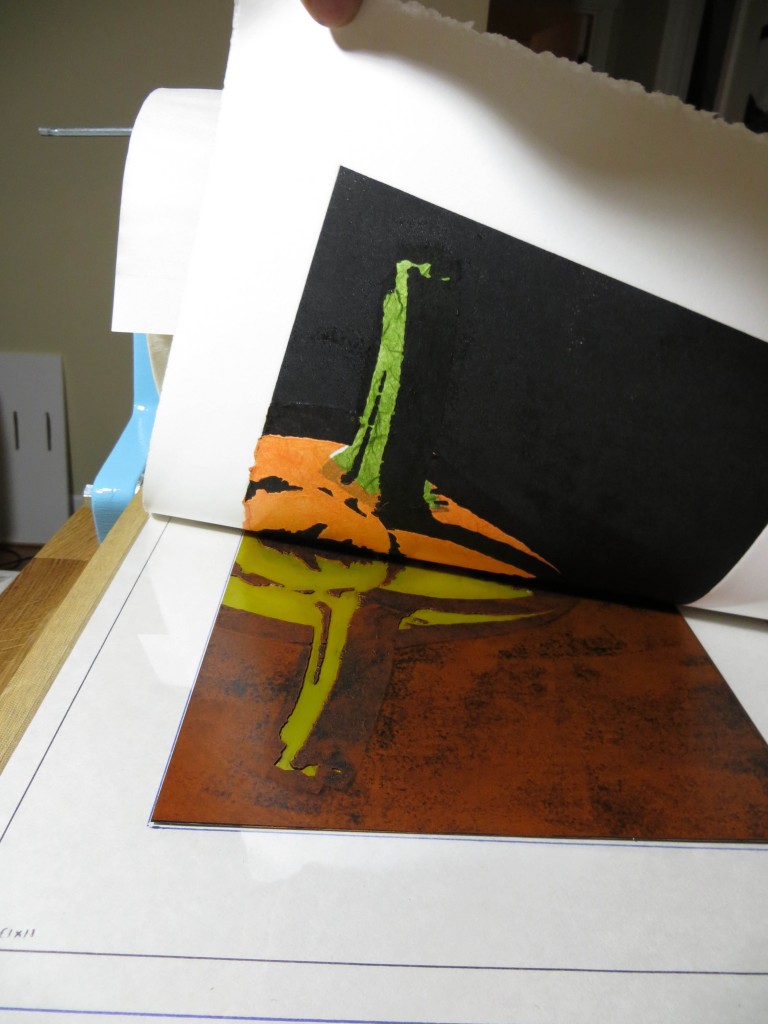

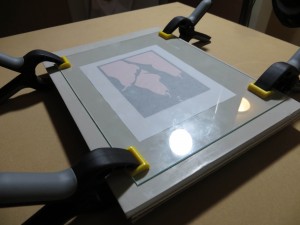

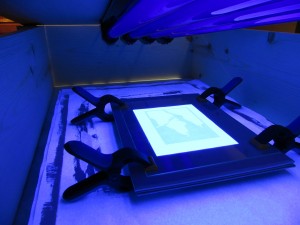

I had my first success with the larger, 8×10″ plates using a black adhesive vinyl stencil affixed to a sheet of glass. The black adhesive vinyl is completely opaque and the glass is clear and flat. The process I used was to paint a positive image with gouache on Bristol, then scan it, negate it in PhotoShop, then convert to outlines in Illustrator, then cut a vinyl stencil with a Silhouette craft cutting machine.

Adhesive vinyl on glass gave me a plate that was perfectly flat with very high contrast.

The process produced beautiful plates, but it was very time consuming and expensive and I felt removed from the artistic process as I spent most of my time messing around with pixels in PhotoShop and teasing the Silhouette machine to cut fine detail without jamming.

I’m glad that I now have a solid understanding of the factors that drive the quality of a relief plate and my hope is that I can use this knowledge to come up with a simpler, more artistic platemaking process.