One challenge I’ve encountered with linocut prints is transferring my design to the block of linoleum. In the past I’ve used Saral and Richeson transfer papers, but I was never happy with the amount of detail that would be lost as I traced my design with a ball point pen. I’d read about ways to transfer a laser print or photocopy directly using nail polish remover or ChartPak blending markers as a solvent, but I never managed to get these methods to work, probably because the toner or the solvents have been reformulated.

Today I stumbled upon another technique which is simple, seems foolproof, and really works. The idea is to use an inkjet printer on a piece of slippery, non-absorbant paper. Since the ink doesn’t soak into the paper, it can be easily transferred onto another surface. McClain’s actually sells special paper that works this way, but it turns out you can get the same effect with freezer paper from your local supermarket. Here’s an outline of the process:

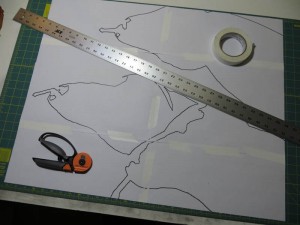

Before printing, I used spray adhesive to glue the freezer paper to a piece of regular printer paper. This adds a bit of stiffness to prevent curling and it gives the printer a bit more traction.

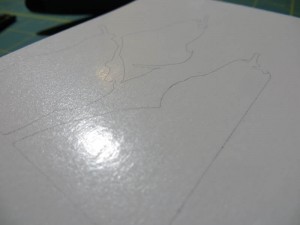

This is the freezer paper right after it came out of the printer. The lines are crisp and I had no problems with smearing or jamming.

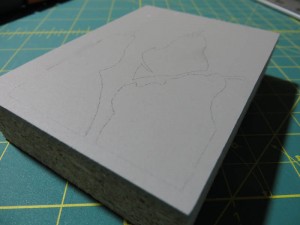

I used my inexpensive Speedball baren to transfer the wet ink from the freezer paper to the linoleum.

The fine lines transferred perfectly and they seem fairly robust. I attempted to wipe away a line on the left side of the block immediately after the transfer and it only smudged a bit.