The Glen Alps press presented a bit of challenge when it came time to move it from Vashon Island to my studio on the mainland, but this was also part of the appeal. Had I purchased a new press, the manufacturer would have arranged for a motor freight company to drive it to my studio and drop it off with a forklift. In the case of the Glen Alps press, I could have hired movers, but the cost would have been exorbitant, and I relished the idea of an adventure on the ferry and a challenging engineering project.

Fortunately Tom, the seller, had a lot of experience moving heavy items by hand, and together we were able to come up with a pretty good plan. The idea was to use sections of ¾” steel gas line pipes as rollers to move the press across the shop to a truck with a liftgate. This worked out pretty well, taking a couple of hours for three of us to load the press. The main challenges were getting the press up a 3” ramp at the edge of the liftgate and rolling the press across the gaps between the liftgate and the truck bed.

We used a 4” x 4” x 8’ board as a pry bar to get the press onto the rollers and to turn the press and get it moving. When we got to the ramp, we had to pry the press up a half an inch at a time and build up a stack of boards underneath until the press was as high as the top of the ramp. We used a block and tackle to pull the press on its rollers into the truck and used the pry bar to help us across the cracks.

My friend, Kevin, a third year student from the Aristides Atelier, helped me unload the press. Since there were only two of us, I rented a pallet jack and this greatly simplified the unloading.

Brains are more important that brawn when moving heavy objects by hand. The reason is that in many cases you and your helpers won’t be strong enough to rectify the situation if the load gets off balance and starts to tip over or rolls away from you on a ramp. The key is to think everything through before starting and then move inch by inch while constantly communicating and reevaluating the situation. You need contingency plans in case you get stuck – every move should be reversible. Also, keep fingers and toes and larger limbs well away from the load and anywhere the load might go if a support failed. Avoid applying strong and abrupt forces – it is easy to pull a muscle or push the load into a dangerous position.

The photos below tell the story of the press’s journey from Vashon Island to my studio.

I set out right after the morning rush hour to pick up the press. The trip involved a ride on the Vashon Island Ferry. It was a bit of a squeeze getting the truck onto the ferry, but that was nothing compared to the ticket booth which had about 2″ clearance on either side. I also got to learn about air brakes. It turns out that the truck’s air pressure will deplete completely if you are sitting motionless, say in a line to board a ferry, and you leave you foot on the brake. This approach works fine in a car, but in a truck with air brakes, you need to go into park from time to time to let the air pressure build up.

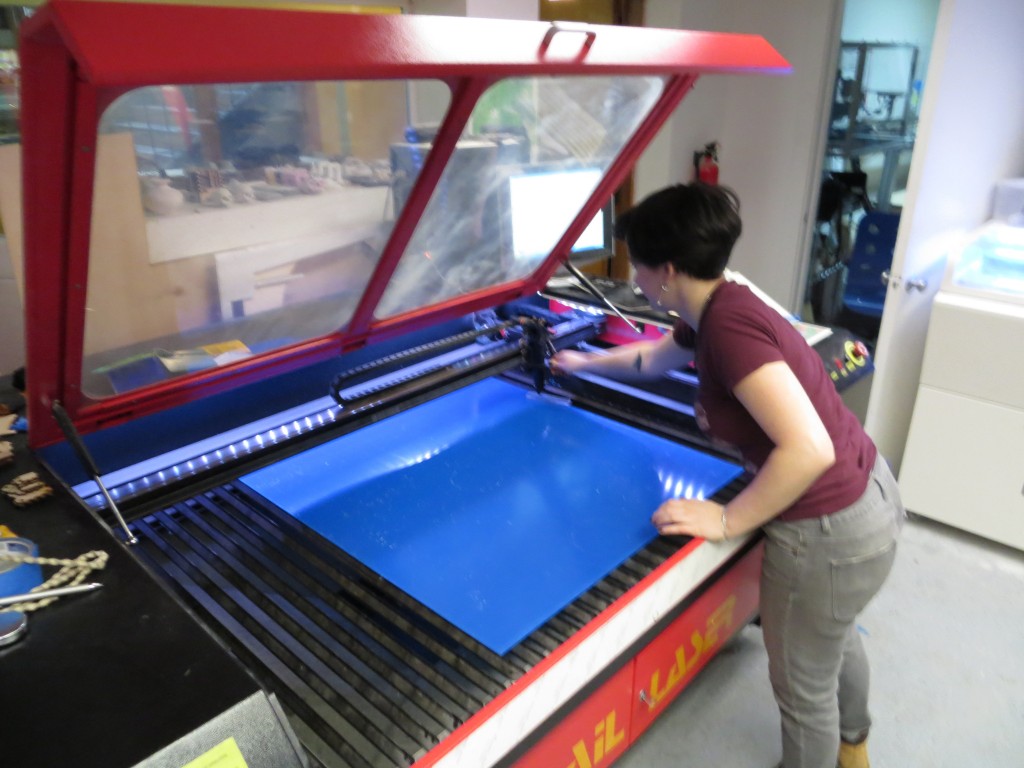

Here is Tom’s shop on Vashon Island. After a bunch of backing and filling, the truck was ready for loading.

We used four pieces of 3/4″ steel gas pipe as rollers to move the press out of its old home. The rollers worked really well when moving the press straight ahead. Turns were another story altogether. We used an eight foot long 4×4 as a pry bar to rotate the press a few degrees at a time.

This eight foot long 4×4 came in handy as a pry bar for putting the press on the rollers and moving it onto the lift gate.

After about an hour of work, we managed to wrestle the press onto the lift gate. The blocks of wood on the ground were used to raise the press up to the level of the lift gate. We’d pry the press up with the 4×4, insert more blocks, and repeat until it was 3″ off the ground.

Tom and Mary pose with the press that they have owned since Glen Alps built it for them in the 70s.

Wedges keep the press from rolling while I pull the truck out from under the workshop roof.

Once the truck was clear of the workshop, it was pretty easy to run the lift up to the level of the truck bed. We used a block and tackle to pull the press into the truck.

The press is secure and I’m ready to head back across the Puget Sound.

Waiting for the ferry.

There’s not a lot of room for the truck in the narrow ferry lanes. Fortunately the lane to my left was not in use.

Passing the other ferry on the way home.

The truck barely clears the roof of the ferry.

My friend Kevin from the Aristides Atelier helped me unload the press. Kevin is a 3rd year student. His dog, Bo, came along to give moral support.

I’ve backed the truck right up to my studio and we’re ready to unload. After the morning’s adventure in loading, I decided to borrow a pallet jack which greatly simplified the unloading.

Here’s a closeup of the pallet jack in action. It takes five pumps of the handle to lift the press and it can be gently lowered with the flick of a switch. Kevin is behind the press, prying with a 4×4 while I pull the jack from the front.

The main challenge in unloading was that the truck bed tilted down towards the lift gate. Our fear was that if we lost control of the press it could shoot off the back and fall to the ground. In the end we used a tie down strap to belay the press from above and we placed a 4×4 at the end of the gate to act as a barrier in case the strap failed. Before starting we made sure that we were strong enough to push the press back up hill and into the truck in case we got the press halfway out and ran into a problem. It turned out to be simple matter to ease the press down inch by inch and we had excellent control the entire time.

This shot gives a good idea of the slope we were working with. I am beginning to jack up the press so that its entire weight rests on the wheels of the pallet jack. The jack works like those long-handled automotive jacks. It takes about five pumps of the lever to lift the press completely off the ground. Note the 4×4 jammed against the chains. We placed it there in an abundance of caution to catch the press if it suddenly started rolling and the strap failed to hold it.

A brief pause for a celebratory photograph now that the press is safely on the lift and halfway down to the ground. The hard work is mostly behind us and we’ve safely dealt with the biggest risks.

The press is safely on the ground and ready to roll into the studio. The only remaining challenge is to work the press off of the lift gate and keep from getting stuck when it high sides. We were able to get across the edge of the ramp by adjusting the pallet jack height, why levering the press forward with the 4×4.

The press looks great in its new home! Now I just need to get some big felts and I will be ready to print.