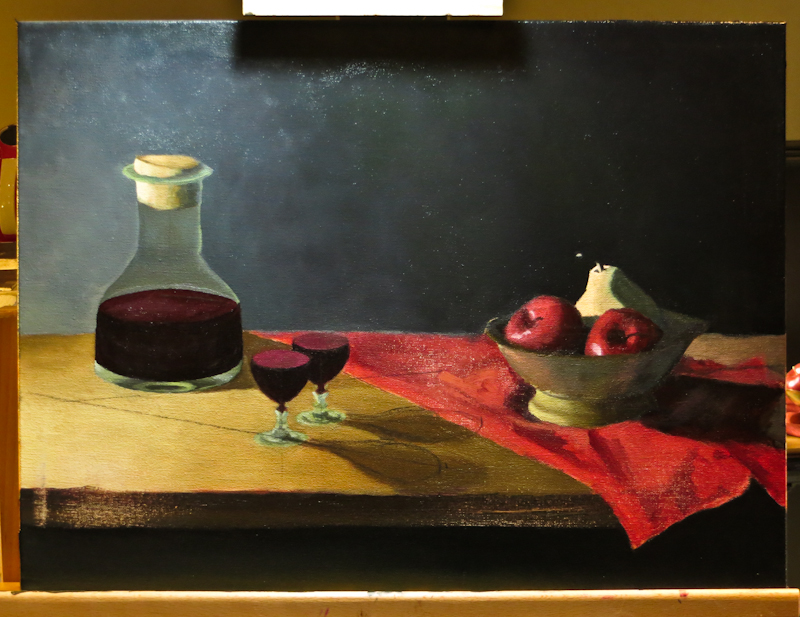

Imagine a sunset at the end of a crystal clear day. The sky directly overhead is a deep blue that gradually fades to yellow along the horizon. If the air is clear enough, there will be no reds or oranges – just blues and yellows.

How would you go about painting such a lovely view? This is a question I have pondered since I began painting. Some of my recent color gradient printing experiments led to an interesting insight.

The challenge in painting a blue-to-yellow gradient is, as every school child knows, that yellow and blue paints combine to make green. If you start with blue at the top of the canvas and work your way down while increasing the yellow and decreasing the blue, you will get a lot of green in the sky. During a yellow-blue sunset, you may see some green in the sky, but not nearly as much as you will get by mixing yellow and blue paint on the canvas.

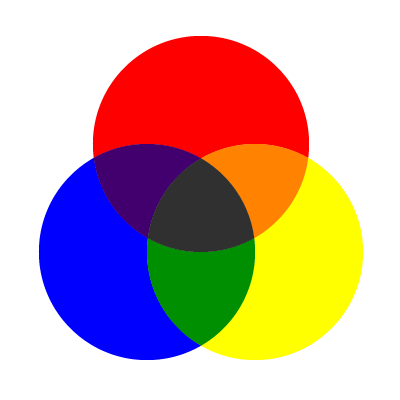

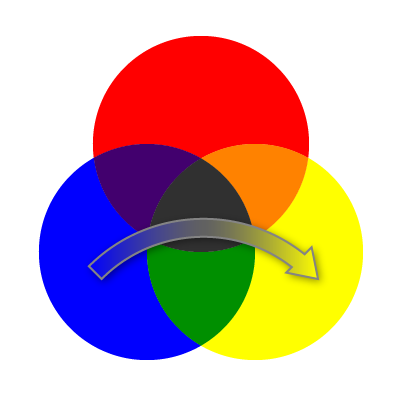

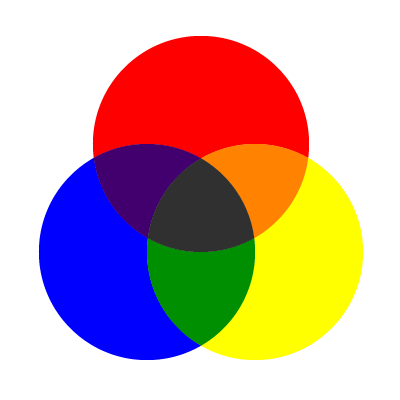

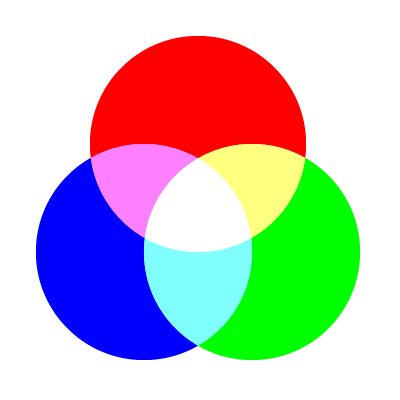

The reason the green appears is that paint mixing works on the principle of the subtractive color model. In the subtractive color model, each pigment or dye in the mixture absorbs and subtracts out part of the spectrum. Combine more colors, and more of the spectrum is removed, leading to darker colors. Combine enough colors and you will get a dark gray.

For a long time, I thought the only way to get a yellow-blue gradient with no greens was to gradually add orange to the blue until it desaturated to gray and then remove violet (or add yellow) until the gray transitioned to yellow. This will make a smooth gradient with no green, but it’s not guaranteed to capture the luminous essence of a sunset.

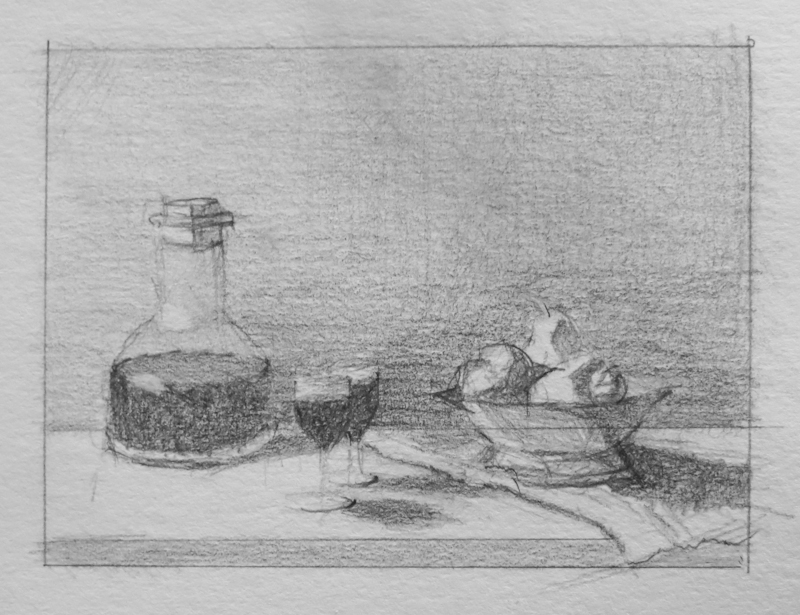

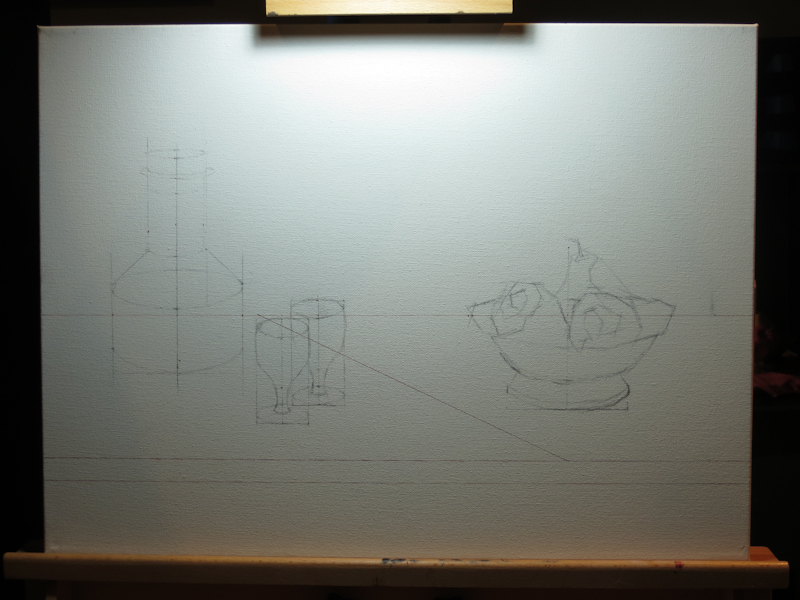

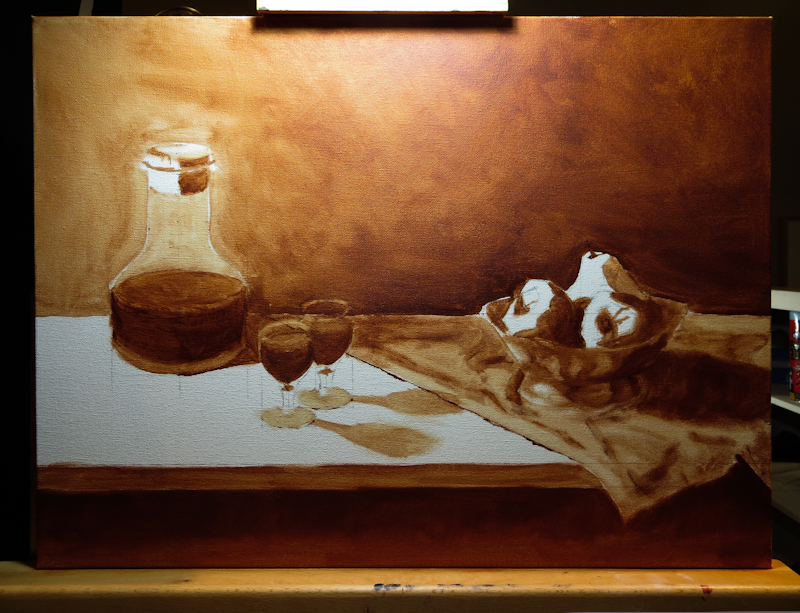

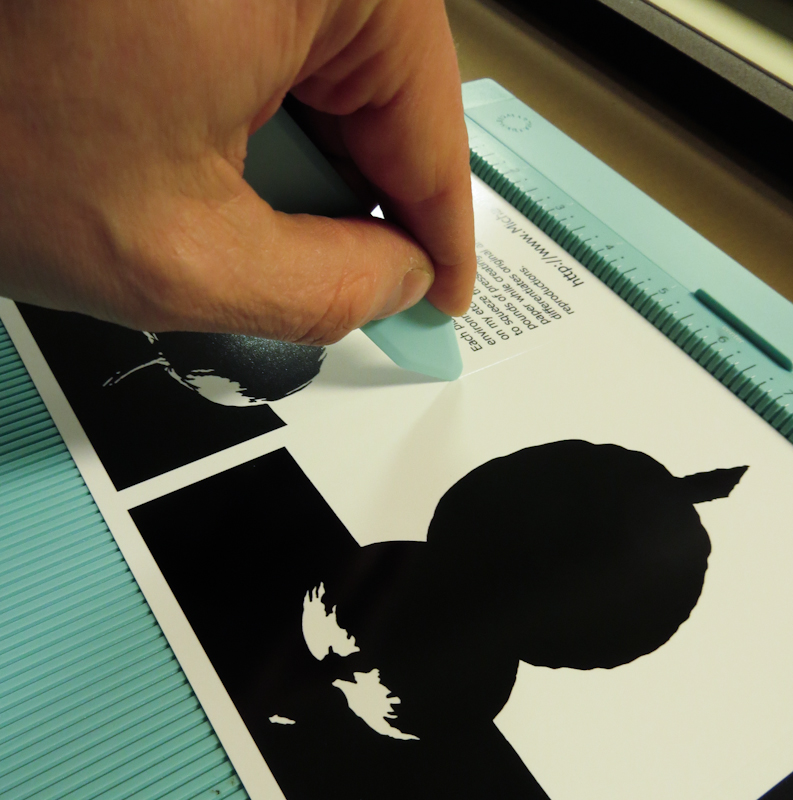

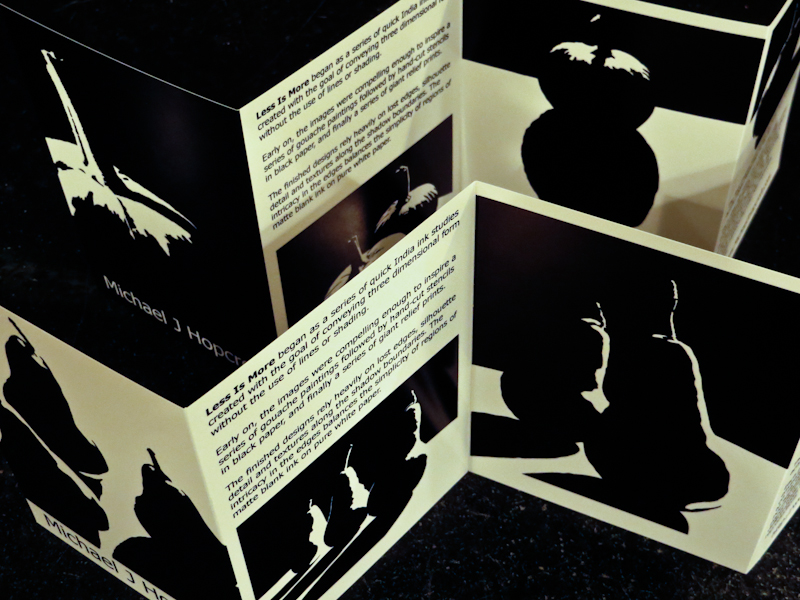

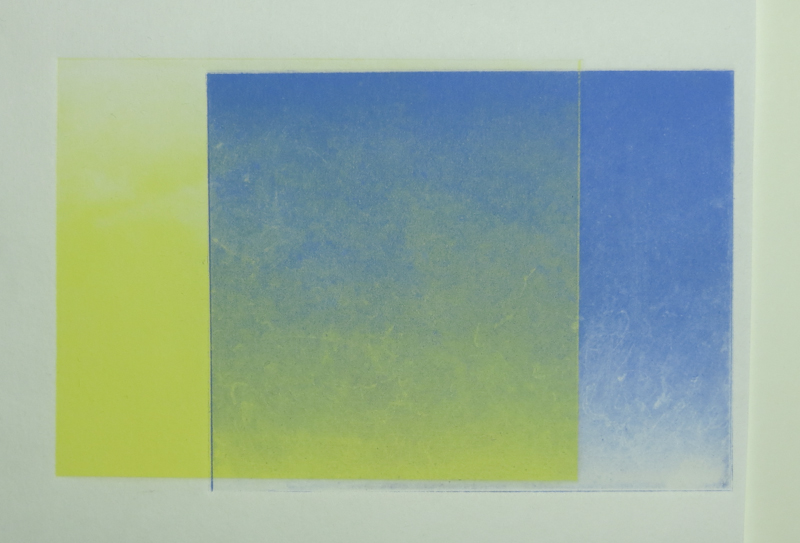

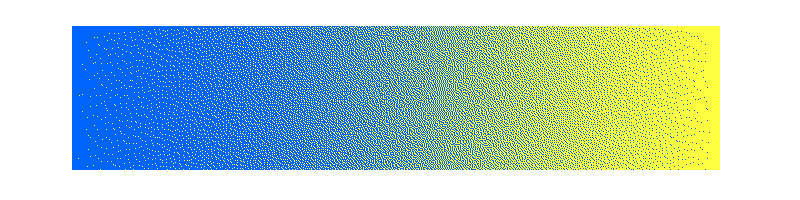

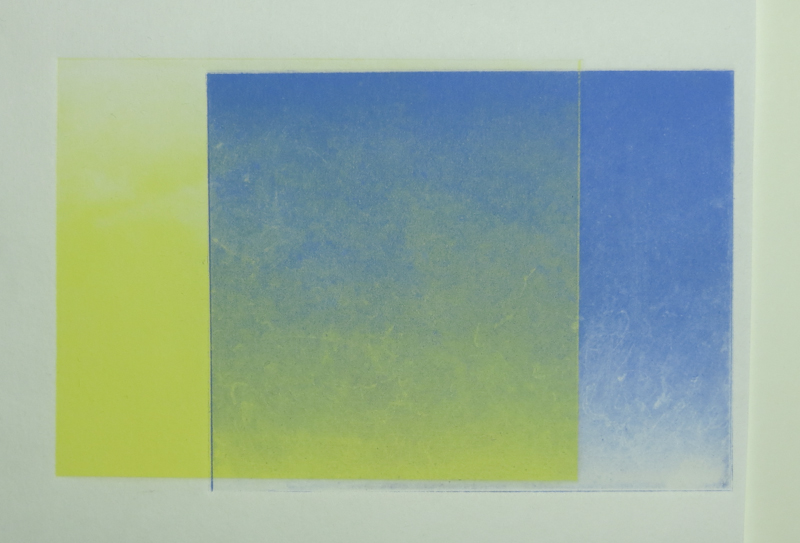

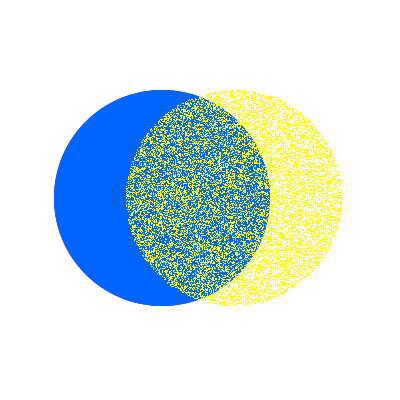

My insight came when I tried printing a blue-to-white gradient on top of a white-to-yellow gradient. I was using an opaque blue ink on top of dry yellow ink, so there was no opportunity for subtractive mixing. Here’s what I got:

As you can see, there is no green! The colors blend directly from blue to yellow. What’s going on? The colors in the print are optically blending. White light that falls on the pigment is reflected back as either blue or yellow. When these two colors fall onto adjacent cone cells in the retina, they create a sensation that simultaneously conveys blue and yellow. The perceived color is a bright neutral, that is warmer or cooler depending on the relative strengths of the yellow and blue pigments.

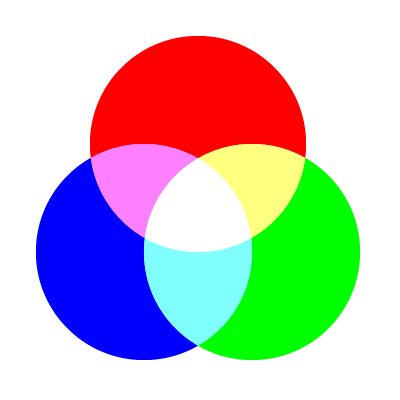

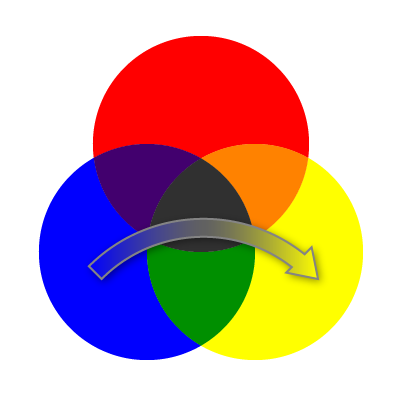

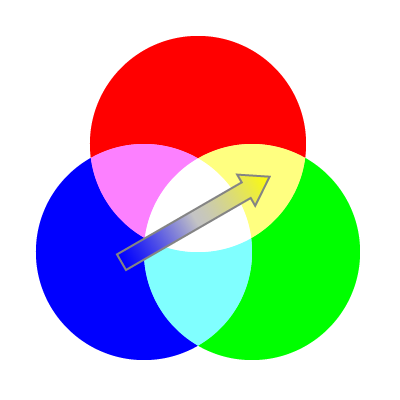

The colors in a sunset work the same way. Blue light from the sky blends on the retina with yellow light from the sun to form a bright neutral. Both the print and the sunset are examples of the additive color model.

In the additive color model, blue and yellow are complementaries that combine to form a neutral that is brighter than either color on its own. Optical blending, which is based on the principle of additive color, allows us to go directly from blue to yellow without creating green.

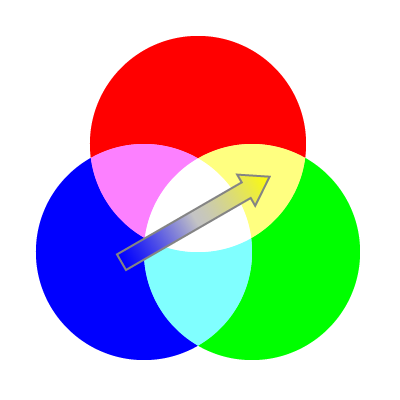

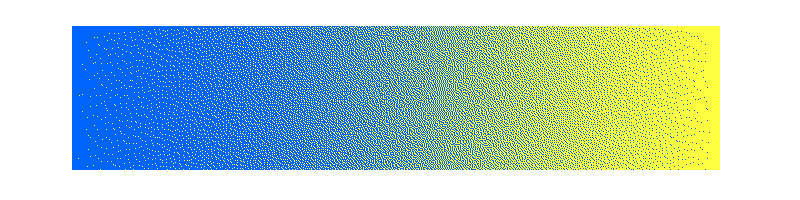

Here’s an example of optical blending in a blue-to-yellow gradient.

We see optical blending every day on computer screens and printed items where the images are made up of millions of small pixels or dots. It turns out that we can get this effect in paint as well, using a technique called scumbling.

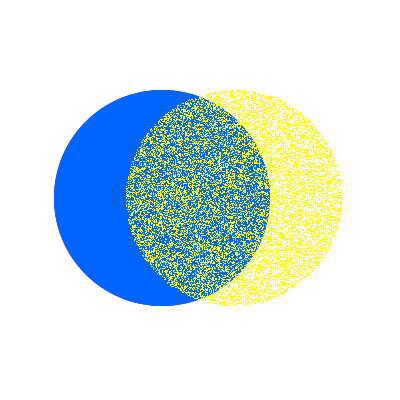

The basic idea behind scumbling is the same as my printing experiment. A broken pattern of opaque paint is applied on top of a layer of dry paint. The dot pattern in the top layer is created with a dry, lightly loaded brush, that just barely scrapes across the surface, leaving an irregular pattern with lots of gaps where the underlying paint shows through. If you were to scumble opaque yellow paint over dry blue paint, it would look something like the image below.

We’ve seen that subtractive color model governs the blending of wet paint, while the additive color model governs optical mixing techniques like scumbling. When painting a scene that uses optical mixing in the real world, it helps to consider optical mixing as a painting technique.

Further reading: