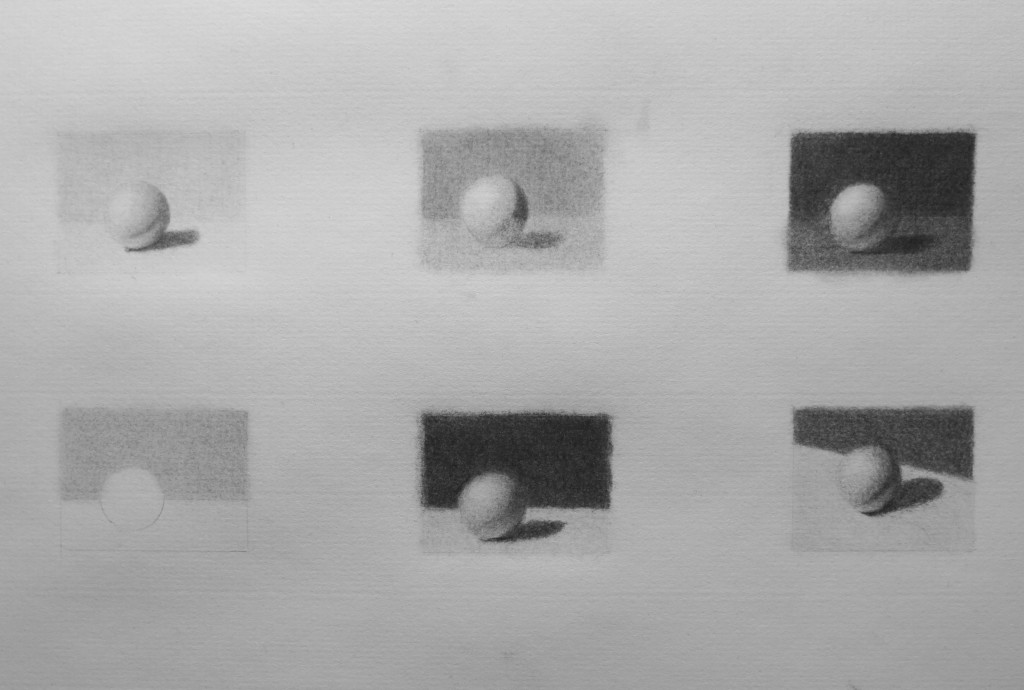

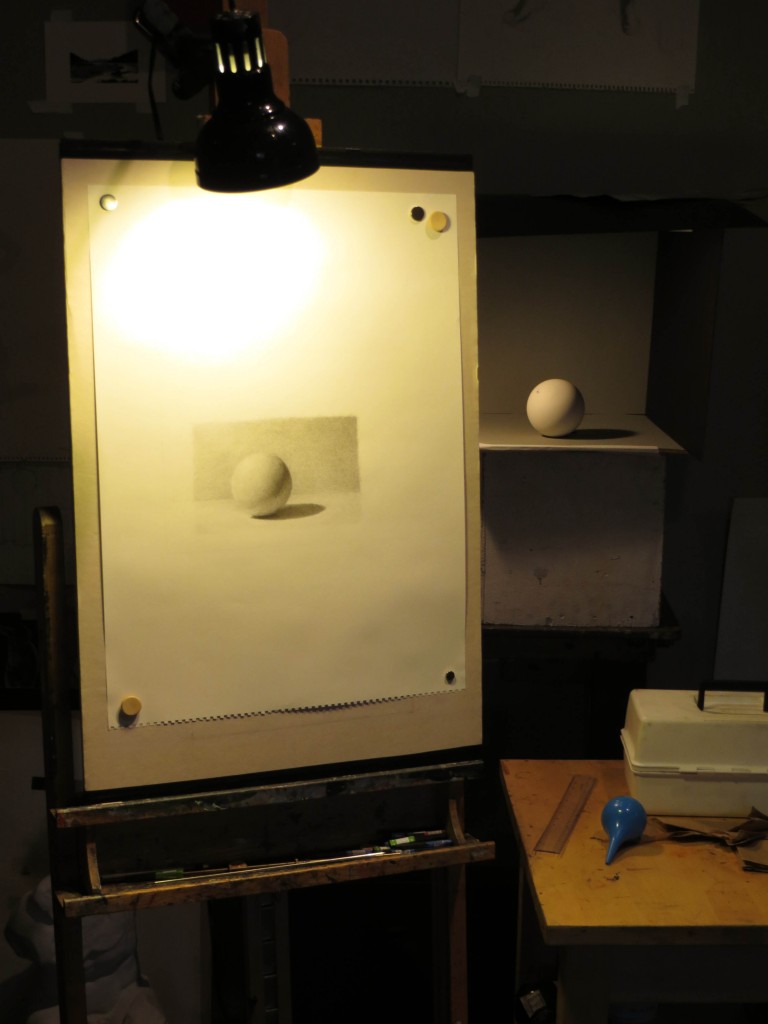

I’m on my third attempt at rendering a sphere and my rendering has really improved. Most of the time I am able to get a smooth tone on top of the textured lines in the Strathmore paper. My paper is no longer turning to felt from abrasion, and I no longer create visible strokes in the drawing. Here are a few things I’ve learned:

- Work very slowly, adding charcoal a molecule at a time.

- Make multiple passes, moving the charcoal in many different directions.

- Don’t move the charcoal quickly because the hard impact with ridges will leave marks.

- Keep the stick of charcoal close to perpendicular to the paper so that only the point touches – don’t lay the charcoal on its side.

- It is essential that you sharpen the charcoal as you go – sometimes every few minutes. You can sometimes sharpen the stick on the paper as you draw by rotating it, but when you hit a soft part of the stick and the point dulls you will need to resort to sandpaper to restore the fine point.

- Lift off dark flecks of charcoal with a tortillon folded from newsprint or paper towels.

- Also use the tortillon to smooth out any ridges that appear.

- Don’t use the tortillon to smudge the charcoal in attempt to get a smooth tone. This will break down the paper and the smudge doesn’t look as good as a hand-rendered tone. The tortillon should only be used to move grains of charcoal from one place to another.

- Often flaws are more apparent from a distance. I am near sighted and find that if I remove my glasses I can easily spot light and dark patches that I can’t see with focused vision.

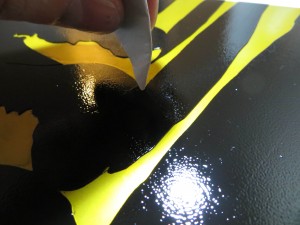

My renderings are still a bit sparkly. If you look at them closeup, you will see lots of black dots of charcoal and white patches without charcoal. Some of my classmates in the atelier are able to make their drawings look like airbrush paintings. I still have a ways to go, both in quality, and in rendering speed.

This is a closeup of the sphere, the table it sits on, the core and cast shadows, and the background. My rendering has improved to the point where the charcoal is fairly smooth, even on textured paper.

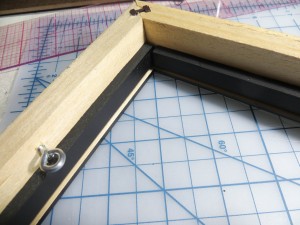

In this picture you can see the ridges in the paper. My technique has now improved to the point where the charcoal stays smooth across the rigdes and valleys. The lines you are seeing are the shadows cast by the ridges.