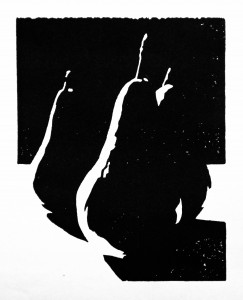

I’ve been having so much fun with the linocut prints that I pitched the idea as a family Thanksgiving activity. We all spent the afternoon listening to music, nibbling on appetizers and taking occasional breaks to carve our blocks and pull prints. I did this quick study of pears intended for a holiday card. The idea has promise, but I’m not really sold on the bits of light creeping around the right side of the middle and right pears. Next time I will do a gouache study before carving the block.

Printing notes: the proof below is actually on newsprint which performed better than the Daniel Smith Lennox paper. I went back and looked at my pumpkin print on Lennox and found that it suffered from the same problems I encountered with the pear – the ink sits high on the surface and it flows around, obscurring fine detail.